In mid-December 2020, I was interviewed by Brenda Sherwood, a student in the Comics and Digital Culture course taught by Professor Michael Jones at University of Toronto. We are reprinting the piece here with kind permission. We discussed a lot of topics--comics, art history, current and future projects...please enjoy:

So Many Ideas: Interview with Award Winning American Cartoonist Paul Pope

By Brenda Sherwood

No masters. That is part of Paul’s philosophy on life. He has exceptional memory and can recite anything. A self taught comic illustrator artist who worked hard to get where he is today. He is described as an American alternative comic book writer/artist. He studied at Ohio State University and then transferred through SUNY Syracuse to study art history and painting in London UK. This was 1988-1995. From there, he started working first in Japan for Kodansha (writing and drawing Manga), and later primarily for DC Comics (Batman). His latest graphic novel, Battling Boy (First-Second Books), the first of a 2-part epic storyline, debuted at #1 on NY Times best seller list. In 2010, he was officiated as a Master Artist at Atlantic Center for the Arts (ACA). One of his earlier works, the self-pubished “THB” (1995-2007) still has a substantial fanbase. He is currently working on the second Battling Boy volume, as well as a project about dream analysis for Dargaud Editions (France), called Psychenaut.

Paul says he contemplates eventually publishing a guide to creating comics, a "Tao of comics," a blueprint for how to create story and illustrations for comics narratives, and how to sustain the lifestyle and mindset to make that happen. He has so many ideas, organized and ready to materialize. Paul tends to prefer to work alone and does not want an assistant or apprentice, so the only way someone will learn his craft is through a book he writes or interviews such as this. His secret is being healthy, no drugs, no smoking, exercising (he prefers rowing and swimming), always seeking a state of peace and awareness through study and art.

Paul Pope sat through a two hour-long interview with me, a student in the Comics and Digital Course taught by Michael Jones at Sheridan College as part of a program at University of Toronto, to discuss his view on comic illustration, influences of art history and Manga as well as future projects.

B: Tell me about yourself, growing up, and your philosophy on comics and life.

P: I grew up as a "Latch Key" kid in a more-or-less Lutheran home, read the Bible, read comics, read the encylopedia, Carl Jung--read everything I could find. I consider myself to be a classical humanist who still uses a brush and ink to draw. I believe an artist should not be defined by their craft. Why not go from doing comics to making a short film or poetry? Its all about expression. Comics are a combination of a lot of elements, film, music, literature. For comics, I believe there is a distinction between storytelling and psyche. You must place the audience within the psyche of the character, and the story is about that character's journey.

I draw with analogue tools, with a brush and pencils and pens, and was raised looking at European art. I trained in Japan and generally don't use a computer to do my work. I keep a close circle of friends in the industry. A lot of people in the industry do use computers to draw, but I am of the old school, like Kirby or the other old school cartoonists. Its about committing to putting a line down, even if it takes longer to do so. And not allowing yourself a chance to edit/delete until the drawing is perfect, which is what digital drawing feels like to me. I studied Japanese calligraphy whie in Tokyo, which helped me to build up a confidence of mark making that can make a drawing beautiful. With a brush, you need to be calm and sure of the mark, because it's very hard to redo once the mark is made.

B: What was your inspiration to start drawing? Did you draw your own comics as a kid? and how did you develop it to what it is today.

P: I grew up in Ohio and started drawing as a kid. I didn't have a lot of friends becasue we moved around a lot, so I created an imaginary world that I lived in, and put it on paper. THB is one of my earliest comic novels, I published it at age 25 even though I first started dreaming it up as early as when I was 16 or 17. It will be eventually collected and finished for First Second Books, after my current project (Battling Boy) is completed.

I learned how to draw for comics through repetition. Drawing, again and again, and that developed my illustrations to what you see today.

With Jack Kirby, although he's been a huge influence to me now, I grew up thinking that his artwork was grotesque. I actually hated his drawings, and it took me a long time to crack his code in creating comics. I saw his stories as complicated, his work as flat, concepts being too big and hard to attain. Back then the comic medium was seen as cheap, as they only cost 25 cents on a newsstand. So, growing up I had to make a decision to either buy a chocolate bar or a comic book by Kirby, as they were both 25 cents. I usually went for comics, and always seemed to gravitate to Kirby, although his work was puzzling to me. Now I view Kirby as one of the prime architects of the language of American comics, the brain of comics, a billion-dollar machine.

I feel that in his time, Kirby never got the respect he deserved or the money for the brilliant creations that he made. At the end of the day he defined American Comics, whereas the more famous Stan Lee popularized comics, and in a way, I guess he was the Walt Disney guy, the man who helped to create a dramatic shift in comics. Lee helped the perception of comics from ‘trash’ to a major piece of popular culture. So that's a real achievement.

B: When did the idea of comics as a vocation come to mind?

P: The idea of comics as a vocation came to mind while I was in school at Ohio State University. I was only 21, job opportunities were limited. It was either become a bartender or an academic, so I decided become a cartoonist. In between, I worked as a landscaper, in restaurant resoration for a brief time, and then as a tech at a printing press, mainly in the camera department and in print pre-production. It's one reason I've gravitated toward silkscreen printing as time went on. I like making things by hand.

B: How and when did you get influenced by Italian cartoons: as you said…’I believe in black and white comics, coming from the Italian school of cartooning.’

P: I found Italian and French cartoonists through Heavy Metal magazine. Heavy Metal in the early 80s was publishing some of the best comics and graphic stories in the world. I was always intrigued with strong black and white brush drawings. I think, eventually, I realized I really liked Kirby because of his lines not just for his drawings. I enjoyed looking at his lines and I decided this is what I wanted to emulate in my comics. To me, the story of comics is about the mark making. I feel it is heroic to make art, as there are craftspeople, artists, and the craft, the medium. Basically, it comes down to your ideas. I want to have drawings, actual drawings not digital drawings, that represent time and place and mark making. And from there, the story to me decides the kind of line I create. Every story needs something a bit different.

With a printing press, you can reproduce anything, it does not matter what the subject is. So today it is brush, ink, and paper, next it's the printing press, ink and paper reproducing the drawing done yesterday.

B: How do your studies in art history affect your illustrations as of today? Which artists or century influence you the most? Do you see some of your panels emulating a painting?

P: Although it has been many years since I taught a residency at ACA or conducted classes and lectures at universities or conferences, my studies in Art History still affect me until today in how I create compostions or employ styles. To me symbolism can represent ideas, which is one thing, I use that a lot, but literal depiction is another thing. Early in my career, my inspirations for compositions came from Edward Hoppper and Caravaggio, and I studied them both carefully. In Heavy Liquid, one of my full-page panels is devoted to a scene where ‘S’ is walking in the rain. My inspiration for this illustration is from Paris Street, Rainy Day by Gustav Caillebotte, a French painter.

Manga is my key technique in creating panels and pages, as it has the power to train the reader to stop on certain images or image sequences, evoking a reaction or an emotional feeling in a particular way. Manga is great as it places the audience directly in the role of the character. The character appears closer to the reader as they are drawn closer to the picture plane. That is why video games are so popular, they are in the first-person perspective.

In Escapo, Heavy Liquid, and 100%, although it may not look like it on the surface, I try to use Manga techniques, as it forces the reader to stop and look at the artwork in an emotinalized way, and not just "read a comic book." The thing my Japanese editor always said was, in American comics, the point is to show a story where Superman jumps over a tall building. In Manga, the point is to invite the reader into the psyche of Superman, so they can feel for themselves how it feels to jump over a tall building.

B: What do you say to people who don’t identify as creative? How do they think they might tap into their creativity?

P: Well, I think everyone has a soul, inside is a story and the soul has a quiet place, but it is often drowned out by media, Instagram, YouTube, Netflix and politics, all that. This makes it difficult for people to think, to feel and get in touch with the quiet inside yourself.

The Stoics believed genius is a bird that lands on your shoulder. You must become quiet so can hear the creativity and inspiration, it doesn't speak loudly. If the mind is cluttered you cannot hear it. I like that idea. Also, there's so many forms of creativity, it shouldn't just be painters or musicians who're considered "creatives," you know?

B: How does technology figure into your process?

P: I am mainly analogue, so I use as little technology as necessary. I am very serious at maintaining analogue art, drawing by hand with no programs or textures. I developed carpal tunnel in my 30s, so I need to be careful about preserving my wrists. I was able to heal it without surgery. I do OT workouts, take krill oil and a handful of amino acids and suppliments, and use the computer as little as possible. I started rowing to keep my stamina and focus high, because drawing comics is very demanding.

B: What is the work you’ve done that you’re the most excited about?

P: My current work is comics based on dreams, Psychenaut. There is no coherence, it is just purely depictions of a dream state. There is no story or substance. It is a repetition of dream imagery. Very psychedellic. My other major project is Battling Boy, which has taken years to finish, way more than anticipated. But it'll be worth it in the end. It's almost 500 pages long. I'm always most excited about the newest projects, so it's those.

B: What outside of comics inspires your work?

P: Philosophy, food, dreams, Carl Jung, healthy relationships, music...

B: In regard to Heavy Liquid there is lots of pink, greyish blue and red, is this homage to Picasso's Blue and Rose periods and was this your decision or the colorist?

P: Yes, it was a decision to pay homage to Picasso’s Blue and Rose periods in Heavy Liquid. It is done from a perspective of the main character, it presents a point of view of the world, as the main character cannot see green, he can only see red and blue. Since the book deals with veiled references to addiction and lost love, I wanted a palette that was a bit acidic or melacholic to reflect that.

B: In your process of creating a new comic where does the idea of color come in? How much do you play in the choice of color?

P: I think of myself as a director on paper. Paper stories. A cartoonist is also editor, a casting director, cinematographer, lighting person… everything. I ask myself what this or that scene needs in order to create an emotional impact. I think of how I can create high contrast or evoke emotion. I'm also lucky to work with some of the best colorists in the industry, notably Jose Villarrubia and Hilary Sycamore, both of whom are great and very good at adapting my ideas or notes in their own ways. Sometimes I will heavily art direct color, but often I like to use what Jose calls the "postcard technique." I will just describe a scene vividly, maybe with a few colors noted or maybe I'll describe the time of day or the atmosphere, as if I am there, and let them interpret it as they see it.

B: Do you prefer scene to scene transitions or action to action? It seems either way you achieve movement in your panels.

P: I have no preference; it depends on the story. As a cartoonist, I prefer action to action for the more dynamic stories, but it depends. I'd like to use more montage in comics. It's a storyteling technique we sometimes see in film, but not often in comics.

B: Do you use different fonts in each story and within a comic?

P: Regarding the use of fonts in my stories, there is no one way of doing anything. Every story has a different set of requirements. I studied Manga, typography, Will Eisner. I sometimes find American comics too rigid and a bit formulaic. So I try to use other schools or traditions in my comics. I do not feel that I will ever become a teacher. I have met Frank Miller, Mobieus, Alex Toth, and they all say there is no one way of doing things. I believe the minute you do something for money you get lost.

B:In reference to Mccloud’s book ‘Understanding Comics’ would you say given your influences from European comics that you follow the same trend in transition, using action to action, subject to subject, scene to scene, aspect to aspect?

P: I prefer to use aspect to aspect transitions and moment to moment transitions if I had to choose. In regards to what you were citing, that was McCloud's opinion up until 1991. He may've developed his thinking since then, I don't know. I think he's one of the smartest guys working in the field, actually. But I am doing my own thing. There is no one kind of comics industry, there are lots of comics illustrators and writers and artists doing lots of different kinds of work. When Understanding Comics came out initially, it was seen as a first-time intellectual study of the medium and done in the comic medium. It was powerful, now, 30 years later a lot has changed. So maybe he has some new perspectives.

B: You said you spent time in Japan. You were using moment to moment transitions, then introduced to aspect to aspect, which is rare in the west. Do you think there is still a east west split in comics/illustration?

P: Yes, there's a lot of things about Asian comics and painting and drawing and other arts, like traditional Noh Theater or Butoh, that is hard for Westerners to grasp. I've spent now decades studying it. I'm glad I was able to work with one of the biggest and most venerated publishers in Japan, I learned so much. Personally, I like using moment to moment transitions, but I have no preference to what transition I use; it depends on what the comic story requires. I also like aspect to aspect transition as an artist. To me, a lot of personal life is aspect to aspect, so it feels organic. But in storytelling, there is no rigid structure. You often do not know what the story will require until you start.

B: I noticed in Heavy Liquid and Escapo there are quite a lot of panels that are divided up on an angle. What is the objective and is this something you created, as I have not seen this in other comics that I have read? I noticed you did not use it in Battling Boy.

P: In drawing panels on a disjointed angle, it is used as a point of view for the subject matter. As in Escapo, it is the main character's point of view, and I wanted it to be a bit chaotic since the hero is a circus daredevil. For Battling Boy, I took a more conservative approach and used the classical comic panel layout. It is a kids’ superhero [comic] with kid logic and that I want young people to read it and for it to be a bit more classical in its style.

B: On the subject of Battling Boy, is the movie adaptation going forward soon and are you working on volume 4? Are you going to continue collaborating with Hilary Sycamore for the colorist and Mark Siegel for the editing?

P: No news on the film side right now, sadly. Battling Boy was at Paramount from 2008-2018 for Brad Pitt's Plan B production company, we had 11 drafts of the film script and I made a lot of concept art. But that chapter is over now. It's a bit bewildering, we put a lot of work into it and the studio spent a lot of money. But when a new studio head moves in and reviews current projects, they have the option to drop things they don't like for one reason or another. It's just the way the business works. We now have new plans in the works, including a new Battling Boy option at a different studio. And yes, I am going to collaborate with Hilary and Mark again.

B: For Rise of Aurora West, will there be a continuation of this character and is she depicted from someone you know?

P: Yes, there will be a continuation of the character, Aurora West, and she is based on my little sister. She plays a big role in the next Battling Boy book.

B: Are you thinking of creating another comics series based on mythology?

P: Yes, there is another short graphic novel project I have in mind, based again on mythology. I think it will be very surprising.

B: Lastly, do you have any quick advice for aspiring comic book illustrators out there?

P: I would say it's the advice I wish I got, and that's to work on short pieces. Don't do long graphic novels. I see so many young people starting out with the idea to do a long graphic novel, and they do not always work out as intended. I suggest focusing on short comics to get the point across, then move on, and find your voice. Then refine it. Study great short story writers. Stop thinking about celebrities and focus on writing and clear storytelling.

B: Thank you very much Paul for your time.

P: Thank you.

Brenda Sherwood is the producer of award-winning short film The Bellringer, and has won many awards including Best Original Score Music in a Program or Mini-Series from the Academy of Canadian Cinema and Television, Silver Hugo Award from the Chicago Film Festival, Special Jury award at Yorkton Film Festival, Honourable Mention from the Columbus Film Festival and a Finalist Award from the Worldfest Charleston Film Festival. The Bellringer has been showcased in over 23 film festivals internationally. She is presently working on an animated adaption of The Bellringer, and works in broadcast.

Saturday, December 12, 2020

Tuesday, March 7, 2017

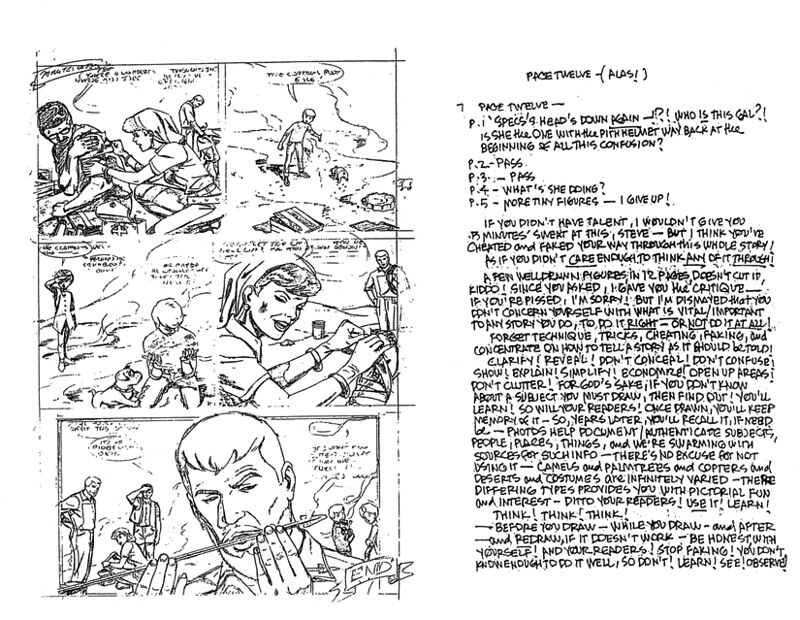

ALEX TOTH

I've been thinking a lot about Alex Toth recently. Needing to get faster and better, there's no more suitable teacher than Alex Toth. By now, probably anybody who cares at all about this kind of thing has seen Toth's handwritten letter to Steve Rude, with the harsh and perceptive critique of Rude's work on JOHNNY QUEST (1987). To be perfectly honest, there is very little in the critique I find myself in disagreement with. I had coincidentally just re-read that story a few days before reading Toth's letter to Rude, so it was very fresh in my mind.

What is invaluable about Toth's letter is that it is a rare opportunity to see an indisputable master of the field deliver a startlingly rough and very unvarnished critique to a younger cartoonist who is himself arguably one of the greatest cartoonists working today.

It is also remarkable because of how caustically brittle and pedantic Toth comes across as sounding.

In many ways, Toth is directly responsible for my life in comics. When I was barely out of my teens, years before I was published, I sent him xeroxes of some of my early work, and he-- incredibly-- took the time to write me back with his methodical criticisms. He was the first person in the field I reached out to, and for years he and I had an epistolary relationship which consisted mainly of me periodically sending him copies of my latest attempts and him sending them back to me covered in big, angry slashes of red. He would redraw my own panel compositions on the backs of the pages to illustrate how he would've laid out a particular scene, how it could all be done so much better and more economically. Each bloodied stack of xeroxes was accompanied by a long, urgent handwritten letter saying in substance what he is saying here to Steve-- THINK BETTER, WORK HARDER, YOU CAN DO BETTER THAN THIS!

These letters were like rocket fuel, or a telescope. Each time I read and re-read them I kept discovering new dimensions of meaning. Each one came in a plain white envelope with a funny little duck scribbled on the side, usually with a blue felt-tip pen. After about three years of this back-and-forth, Toth abruptly told me at the end of one of his letters, literally, "Okay, kid! I've had a bellyful of you! I've done all I can. Come back when you have something worth showing me!" And that was it.

I never wrote him or sent him anything again. I know he'd seen my work over the years and was keeping tabs. But as far as his parting words go, nothing I'd done seemed to live up to his challenge.

I know there are others in the field who had this kind of relationship with Toth over the years. He could be a generous teacher, and he gave much more to the field than he took from it. His letter to Rude is like a snapshot of a long lost relative who has been gone for a long, long time. The reason his words are so harsh is because he knew Rude could take it. His letters to me were more patient, more paternal, although in essence he was saying the exact same thing. He was fond of quoting Isaac Stern, "Make it so simple you can't cheat..."

The other reason his letter to Rude is so harsh is undoubtedly because Toth didn't give a damn if you or me or anybody else liked him or not.

I know a lot-- a LOT-- of people who had gotten close to Toth and eventually wound up getting hurt somehow. He must've been a very difficult person to have as a friend. He had a legendary temper. The things he loved, he loved. The rest of it he couldn't care less about. I had many chances to meet him over the years and never wanted to for this very reason. I didn't want either of us to be disappointed. He was and is too important to me. It's an important lesson to learn early in life, especially in creative fields, one I've applied many times since-- Do Not Meet Your Heroes.

To be perfectly frank, it seems to me that often when young cartoonists say they want critiques what they are really after is praise and flattery and not the truth. I believe just about everything worth saying about comics-- and perhaps even about the entire process of thinking as an artist-- is summed up in those terse words from Toth. Make it so simple you can't cheat. (originally published 12/2006)

Thursday, March 2, 2017

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)